Earth's Habitat Change

Pouchulu architect

9 - Architectural Actions: Survival

To help our Earth re-balancing must be our objective. To stop oil, plastic and chemical pollution, a command. To plant billions of trees, our challenge. The planet will do the rest. It is interesting to observe that survival is more visible onboard a ship, that in any particular architecture. The Argentine aircraft carrier 25 de Mayo pictured below circa 1982 (former UK HMS Venerable R63, and Netherlands HNLMS Karel Doorman R81), seems to be the type of construction -in this case mobile and on water- that could be assimilated as architecture: literrally, a floating piece of land, a platform with a tower on top and infrastructure underneath. I discussed this subject with Sir Peter Cook back in 1998, some afternoon at the Bartlett and, according to Peter, it is possible to define certain kind of ships (in this case, a major one), as a piece of architecture, particularly when is seen from far.

Argentine aircraft carrier 25 de Mayo (former UK HMS Venerable R63, and Netherlands HNLMS Karel Doorman R81), circa 1982.

In fact any mobile construction or machine can show some sort of architectural qualities if certain conditions apply. First, it has to be thought and designed not just with ergonometric and escale parameters, but for an explicit multi-spatial functionality. For instance, a caravan is a vehicle that travels on a route and then stops, opens its back or side doors and suddenly is integrated with the surroundings: then it becomes a temporary camp for its occupants, which is clearly an architecture action; I urge you to watch the beautiful movie Traffic, from Jacques Tati -in fact, you should enjoy and learn from all Tati's movies and if you can, watch them in order. You will notice that this master not only was a filmaker and a comedian... he knew and practiced architecture than the majority of architects-. Second, it should not only offer shelter against weather, but serve to certain specialised living qualities: working, resting, playing; third, it has to be flexible enough to serve different, unexpected or unplanned activities. Third, it should exude some meaning, a message that points either to Nature or the Universe. There are a few architectural principles in history that can clearly define a link to the Cosmos like Organicism, which in many ways has to do with survival, I will explain why.

The spirit of a building is something not difficult to see or perceive... if it has one. In general, classic architecture had a strong link with Nature and mind, expressed in geometry and mathematics; this relation was not only figurative -anthropomorphic language represented in the Greek Orders (Doric, Ionic, Corinthian) but the whole architecture system was based on a repertoire of signs, that referred to proportions and human escale. This is the first principle abandoned by Modern Movement (CIAM, Le Corbusier), however kept by a few masters like Walter Gropius or Richard Neutra, both admirers of Frank Lloyd Wright's work. Second, proportions also had to do with the implicances of a person walking in continuity both in outdoors -or surroundings of the building- and in its interior.

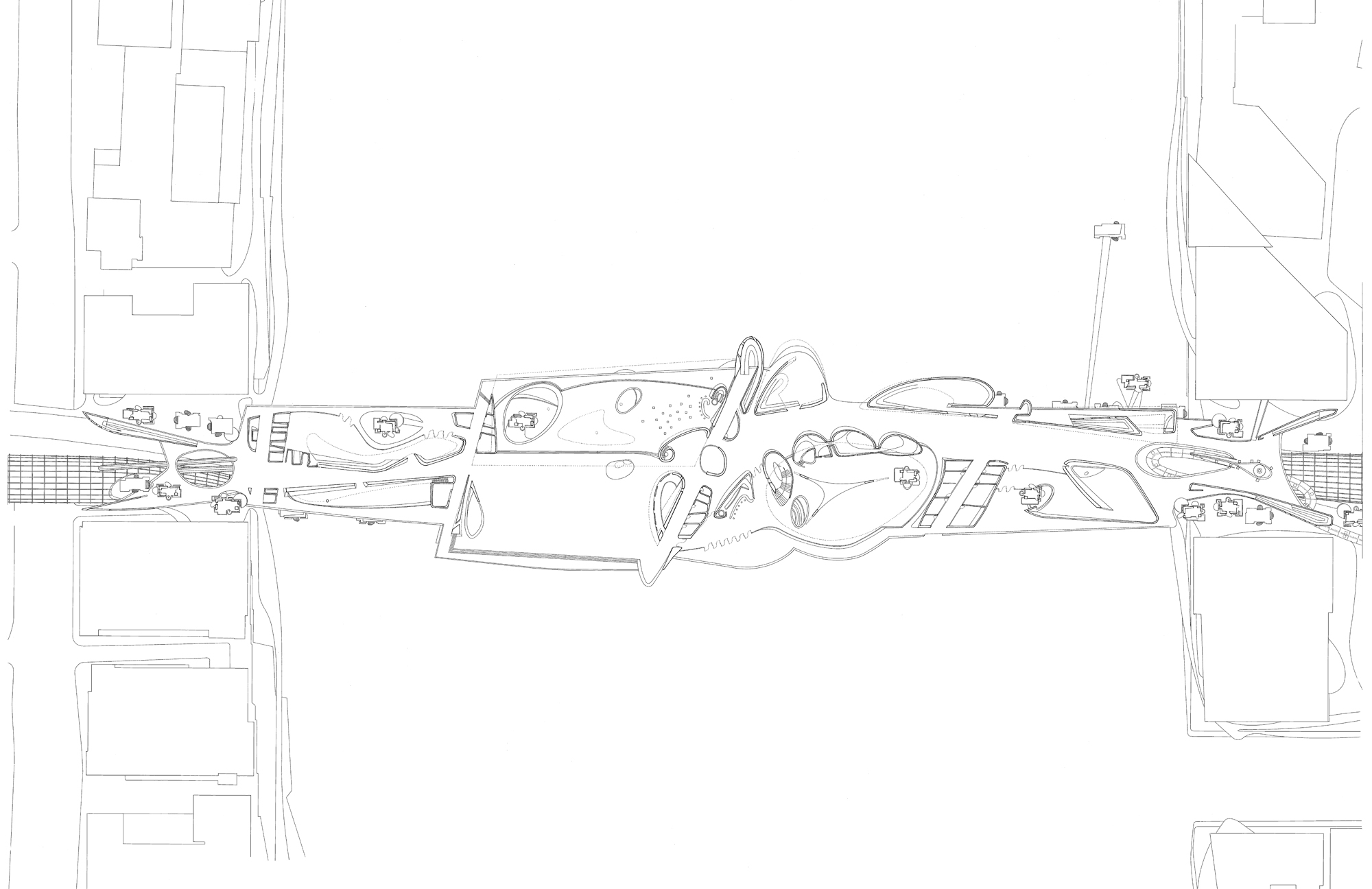

Pouchulu's London Bridge Project, London, UK, 1998, a living bridge (linear city on top) on legs (flats) over a road bridge, connecting the North with the South of London: waiting for sea level rise? Pencil, coloured pencils and oil on Canson.

Classical architecture, from Hellenistic times till the late 19th century was primarily a complex reality perceived and experienced from the point of view of the user. It is not possible to explain the approach to the Parthenon, walking from the Propylaea, passing by minor temples, changing the angles of vision, preparing emotionally in complex intimate perception during minutes and hours, to finally enter the Pathenon, where Athenea goddess' sculpture was standing, I repeat, it is not possible to explain it in any drawing or model representation: you had to walk, and that path was a procession in real time, at a particular moment in the afternoon, in a determined day, architecture was real. We cannot recreate that in a screen, or in any virtual representation, even if we put a helmet and imagine we are there...we are not. Classic architecture had the complexity and beauty of reality, which in the Acroplis included the dramatic qualities of the air, the long perspectives and the effect of mist, the wind, the olive smell, flowers and the humidity of the stones, sound echoes and ambience enhanced by some chords...

Pouchulu's London Bridge Project, London, UK, 1998, the "belly" under the main platform, towards Southwark. Pencil, coloured pencils and oil on Canson.

Classical architecture was represented as a language, not as a metalanguage like today, where we gave up reality and got conformed with representations that simulate and copy reality, impersonating reality, but they are not. Fake spaces that look great on a screen, but mean nothing in reality. Fake materials, pretending to be wood or fibers when they are made of plastic. The discussions, most of the time, assume that we must thank digital hyperrealism capacities (computer generated BIM models, animations), because the process of architectural creation, represented as real, is finished. The results are, to say the least, catastrophic. Built architecture tries to copy or assimilate virtual renderings, not the intentions of the architect's hand. In the classic world, as we pointed in previous chapters, architecture and the urban space started to be figured, suggested by hand-made drawings and then completed and modified during construction thanks to the hands of builders and dozen different artisans' métiers. Therefore, the final result was always richer. This, in the context of professionals and experts that knew how materials worked, how they looked, how they aged. That beauty of reality, so much adored by Romanticism, was emulated for the last time during Brutalism and Structuralism, in the sixties and seventies.

It is sad to see so many noble structures to be demolished... because their concrete became darker and greenish. Clean images produced by industrial prefabricated materials are enhanced by deadly minimalism and perfected by digital images. These, initially belonged -by their own right- to the beautiful aesthetics of cars and machines -precise, straight and polished like never before-. After the extreme cold neatness of digital rendering, the sensitivity of architects evolved into a "plastic" type of reality where materials have to be glossy and smooth, they cannot have any smell, age or become deteriorated. At the end, by rejecting materiality, we are denying our father, Time. Like many up-nose upper-class soup-flavoured old women, our buildings have plastic surgery on a regular basis... How beautiful was the trace of time in our cities! In that sense, only a few places, like Rome, Venice, parts of Rio de Janeiro, Buenos Aires, remind how the old world looked like. Central New York and London became too neat... new buildings are excessively clean and glossy. Now, why this has to do with survival? It is simple. The more input and effort we put in forcing the response of a building against time, the more expensive and anti-ecological it becomes. Indeed, materials age and deteriorate, even stone, but one thing is to assume we must replace our whole environment after a few years because it looks old or "out of fashion", another thing is to admit we must replace parts here and there to extend its life-span. Minimalism, a coward form of Idealism, is anti-ecological and against the notion of survival.

Pouchulu's London Bridge Project, London, UK, 1998, main level, upper platform floor. Ink on film.

Our approach to architecture has to be fully revisited, in times of Habitat Change, in order to define what kind of environment and investment we are willing to offer if we want to become sensitive about our lifestyle in relation with Nature. In the best scenario, we will have to conform with situations where expensive materials and energy, even limited available habitable land will force us to accept original shelter concepts to protect from the elements. We have been extracting materials and destroying forests for many millenia, in the last two hundred years we waisted energy and money in endless useless theoretical discussions about language, images and representation. Time to revisit the work Frank Lloyd Wright, Walter Gropius, Richard Neutra, John Lautner, Louis Kahn, Paul Rudolph, Kenzo Tange, where architecture was still supposed to last hundreds of years, and that's sustainable and ecological: because it lasts.

Ships are mobile shelter, sometimes emulate architecture, floating territories that silently fight for survival against the immense ocean and fierce winds. Because they are made of steel, their lifespan, unfortunately, is short: 30 or 40 years.

Read the next chapter, here.

1 - 2 - 3 - 4- 5 - 6 - 7 - 8 - 9 - 10 - 11 - 12 - 13 - 14 - 15 - 16 - 17 -

Contact

To contact Patricio Pouchulu press here, or send an email to: architect@pouchulu.com

More information available in Deutsch, English, Español & Français at: www.pouchulu.com